The Intercity to Delhi

At 7 in the morning in late October, when Patiala was still sleeping, enveloped in the early morning fog, the few people outside could be seen with shawls trying to beat the mild chill of the Northern Plains, when the streets were still quiet and the harmonious surroundings were not yet invaded by the diesel autos, the few strays still too sleepy to register irritation at the person who trespassed into their territory, Patiala Railway Station was a sharp departure from the above.

The 7:33 Intercity to Delhi would arrive soon.

At first glance Patiala could be easily mistaken for just another small-town railway station – there is no outwardly visible clues to its history or its design. The station serving the capital of the PEPSU region is built perpendicular to the rail line. The platform 1 with its arched steel and tin covering, its pillar designed with circular support is vastly different from other stations of India. The Maharaja had grand plans.

Thapar people rarely take the train to Delhi, preferring the much more comfortable and faster service by the Volvo and Scania buses. Just before vacations, a few of them can be spotted near the place marked for the Chair Car coach, perhaps unable to secure a ticket home due to the rush. A few unfortunate ones whose decision was made on a short notice, thereby missing out on the comforts of the air-conditioned sanctuary but having enough time to book a ticket, gaze into the distance near the front of the station marked for the few reserved coaches.

The arrival of the train was marked by quick and harried activity. The train stops for 2 minutes and today it stopped way before its marked point, making people to run for with luggage on hand and children on other. This bond between the older matured hand and the small tender hand was held tightly. The matured hand has seen much of the world than to allow it to hold the hand lightly. Breaking into a run, I too joined their ranks. My hands instead carrying a bag, the weight of which I believe was mimic my own – the result of a long overdue visit home.

Once inside, I paused to catch my breath. The carriage was moderately empty. I found my window seat, put my bag underneath the seat, my bag pack tucked away safely at the top, sat down and massaged my sore shoulders.

With the blare of the horn, the train started, I looked outside. The platform now deprived of its temporary inhabitants which made it come alive, now went back its unhurried and insipid existence until the arrival of the next train. The lone vendor on the platform was putting back his freshly made pakodas into different compartments of his stall – waiting for the next train to bring passengers. This is all like a clockwork – the stopping of the few passenger trains, opening of the gates, exchange of token – repetitive and monotonous. There is hardly anything exciting happening on the station. Yet, Patiala has its charm.

The brilliant beams of the golden sun gave a splendid shade to the Punjab countryside. At the distance, the yellow fields merged with the slanting rays as if part of a single entity. A low-lying mist overhangs the fields giving the entire setting a hazy, mysterious appearance. The light is welcomed in all quarters in equal measure. Its warmth embraced gleefully in the mild chilly weather. Inside the compartment the fresh and cool crispy air coming in through the open windows made a few wrap their jackets and shawls closer.

The compartment was an old one where two rows of seats face each other as if to facilitate conversations. In 2019, it didn’t. A middle-aged man, balding, small in height with a bandage on his leg and a tiny voice occupied the window seat. From time to time, he kept adjusting his leg to make it a little more comfortable on the hard-cushioned seat. His view was fixed outside, as if thinking about some problem. The trance broken by the calls where he kept mentioning someone his coach number. To my right was well built, lean and tall man. Wearing a red jacket and khaki coloured pants, his grave face made me think him of a police officer on leave. My imagination was given backing when he asked the young man on his opposite to down the glass shutter. ‘It’s cold inside.’ His voice boomed. More like an order than a request. The young man complied after taking some time to register the fact that a protest would be futile.

The Intercity to Delhi travels from the border town of Fazilka to the quarters of Old Delhi, passing through towns which seldom heard of in the context of Punjab. Small towns lying on single track, through which development comes in slowly – often leftovers of the big cities of Jalandhar, Ludhiana and Amritsar. The slow march of development did not hamper the growth of technology among the residents of such towns. In the compartment, most of them were busy on their phones and watching some YouTube video on the moving train. This last bit heralded by the affordable Internet plans – a sight unheard barely 5 years ago. The conversations were negligent. People were trying to catch some sleep broken by their early morning trip to the station, their heads bobbing with the motion of the coach.

A small girl of about 5 or 6 years held the dupatta of her mother’s salwar as she gave the most sweetest smile and tried to sing some Hindi song as she waited for the train to stop at Ambala. Her mother irritated by her younger brother on her shoulder who was constantly trying to break into wail, didn’t pay much attention to her. The father, looking lovingly at his daughter said, ‘Kya hua beta? Bohot pareshan kar rahi hai’ Definitely not meaning the last words.

The arrival at Ambala Cantt saw most of the carriage emptying. The seats quickly taken up by the newcomers without a reserved ticket. The window seat was vacated by the small man and I quickly moved to the most cherished place on a train, lest it be taken by someone. Smells of bread omelette, aloo puri, break pakoda wafted in through the windows. I felt hungry.

The vacant space beside me was taken up by a man in his 50’s wearing a striped blue shirt, deep blue pants and large shell frame glasses. He was carrying a black office going bag. As soon as he sat down, he took out his phone and seldom looked away from it until the TTE asked for his ticket. He kept himself busy texting people on WhatsApp and spent a lot of time to reply to one of his many forwards with the best emoji. In the end he settled for the time and tested one of folded hands and a smiling face. Experimentation can wait. Kept checking back for more replies.

Ambala also brought with it the much needed TTE. The sight of him made many stand up and travel to the end coaches. In such trains, the distinction between the general and reserved coaches are seldom made. One of the young man opposite to me, promptly took a call and pretended to talk while moving away to the door. When the TTE left, he came back. His seat was being kept by his bag. The middle-aged woman from Rajpura travelling alone spoke before giving the TTE a chance.

‘Mere brother Kulvir Singh railway staff hai. Shatabdi mein jaate. Ticket bana do.’

‘Thik hai, thik bana dunga.’

‘Waise mai bhi staff hu.’

The necessary transaction thus completed and uncertainty settled, she went back to her slumbering state. The infelicitous ones kept looking at her with a scorn as they made their way back. Argument was useless.

Outside, the country side changed. From single storied houses without plaster to painted ones and sometimes even having a double story as a major town approach. The approach and the departure from Ambala were marked by such two storied houses, often with a saffron flag lifted on a pole. There was mostly a temple nearby. Sometimes, these houses had the flag of the BJP fluttering, it being barely discernible from the temple ones. The flag of the opposition was nonexistent. Election season has just ended in Haryana.

I found the small-town station, where the train did not stop quainter and cleaner. There was no one except the lone guard who lifted the green flag for the passing train. The stations had the luxury of having flowering plants in comparison to its bigger counterparts. Most often having bougainvillea plants in their pink and yellow in full bloom, overflowing their guarded enclosure.

As the tracks led towards Delhi, the view outside the window acquired an anaemic look. Houses turned increasingly ugly, built on any available land without any thought. Even the fields were layered with hazy fog, refusing to move. The streams passing underneath changed colours from a bluish to a darker shade of green, having an obnoxious stench. The tracks became dusty and a fine layer of dust covered the passengers when an opposite train passed. The view looked heavy, strenuous. I took to sleep at this point.

Panipat saw a deluge of bread pakoda sellers. Bread kha lo. Garam bread le lo. Haanji, garam bread pakode. They arrived in a wave. For a stoppage of only 2 minutes, each tried to convince us to buy their cold, greasy, bland and often unhygienic bread pakoda using their cries as their unique selling points. The one with the most different call, got the most customers. 2 minutes the train stopped and many pakodas were sold. The vision of our PM seems to find its voice in Panipat station.

The Delhi Circular Railway is now mostly a remnant of the past. The stations now empty, people not passengers sitting and staring blankly into the distance, talking. Some smoke cigarettes. They know they won’t be caught. There is no one else. Sometime, the odd local comes, but there are few takers.

The two storied houses gave way to tall, modern buildings. The garbage increased. Cows, people, pigs all scavenging in the same place. At some point, plastic was being burnt. The stench became unbearable. Yet people lived in such squalor, in small, cramped dwellings.

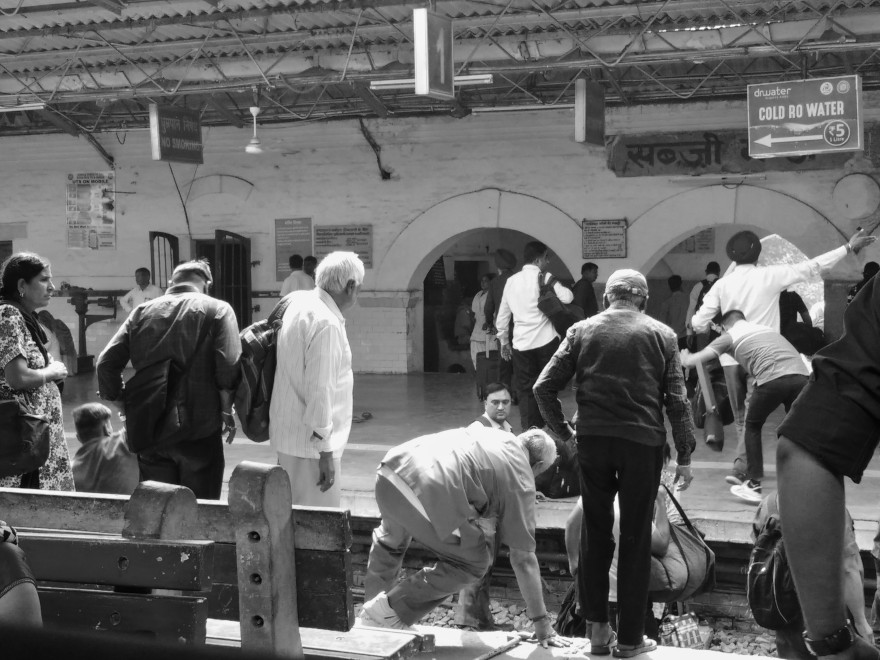

People left at Subzi Mandi. In a daring show of bravery, they jumped onto the tracks to climb on to platform 1 before a train comes. A train did come. The locomotive blaring the horn nonstop which can make even the deaf hear. There is a hope and a prayer in this. Hope that no one comes in between and today no one did.

After Subzi Mandi, the pace slowed down to a crawl. Tall, grey buildings guarded the blackened tracks. Someone got pushed by the luggage near the door. An angry expletive registered the disapproval of the action. Delhi has arrived.

Like it? Subscribe